Gone til November, I mean August, please.

I feel lost this morning. Lost in my thoughts and ideas. I woke and went to sleep over and over again all night long. I am trying to practice listening more but I am also getting distracted more by what I hear. I have my ideas…too many maybe. Not enough maybe.

August says finish what you’ve started so you can go onto your next thing. “You want your next thing, right?????!” He teases.

I am obsessed with the next thing always which is why I think this time around I am being forced to stay still more and not be so obsessed with the next thing of it all.

I started a play. My goal is to get that done by August. I go to Austin next week to listen to the blues (AUGUST’S FAVORITE!) and to hold two book events and to eat new food and see new things but mostly to do nothing.

Spend some time with August Wilson the only man I really trust. A love affair with a dead poet makes it difficult to find a living one to love.

This is good for me because I have to just get started and hold space and not let holding space for others distract me from holding space for me. Don’t let community be my excuse for not seeing what I seek to see. And then I question always the doingness the constant need to people please. Maybe if I could just do less I could hear more. What do you hear now. Now I hear me saying, August, I want to be free. Always the same request. I want to be loved, AUGUST. I want to be free!

“What’s love look like for you today?” He asks.

It’s like I just want to be held real real tight. Not smothered but perhaps mothered. Can’t wait to leave for Austin, maybe I’ll find what I am looking for there.

Seeking fills some sort of need. Deep extended alone time maybe. A way to not be needed. I hate coming back, nothing is ever the same as when I left it. I have to delegate they say. Can I delegate my whole life to someone else. LOL

I will just start over again and just do it myself as usual. How you gon do it yourself, Jeannine. You don’t know what youre doing. And you are leaving. I know enough to get it done until I find someone I can trust.

When I got to Philly, twenty years ago, my friend Omar used to say, “trust no one, bust your gun.” What type of mentality is that, Omar. If I listened to him I would be busting my gun at everyone. But he wasn’t fully wrong. Trust is a big lesson for me. How to trust and how to trust less how to be trusted. I be so trusting. I be like here’s the keys —to everything! Part of that is because I am fearless. I am protected and know nothing can harm me. Not the real me. But some things can make me cry. Make me sad. Flatten me.

Lots of fish in these seas they say. But I don’t like fishing.

Requires so much patience and waiting and throwing back the baby fish that won’t fill me. This is why I have to trust me at least. But I love. I need someone who loves like August Wilson loves me. I need an ugly lover. I want to see your grossest wounds right away. People don’t know, but August is ugly.

I want to hear you weep so I know you can. I want to hear you scream and throw things and curse and be as ugly as can be so we can get that out the way without waiting two years for your ugly self to appear from behind a wall and surprise me. I don’t need no pretty lover. Covered in fluff and eye shadow. I want to see the shadow first so I can see the part no one else sees.

What I am really saying is I want to show someone else my shadow self and let myself be seen. I’ve worn plenty of eye shadow. It makes my eyes heavy. It makes them water. It makes them bleed.

And that gets me to crying right here in my corner on the chair. Cause maybe that is not as true as I wish it were that I want to be seen. SHUT UP & WRITE even if it makes me wail. Sit still. Be quiet. Lock yourself in the closet. SHUT UP. Ok I aint said nothing in 40 minutes. Twenty minutes to go.

I think I can write in environments where others are there. I can definitely write when the other writers are writing. Writing aint as easy as folks wish it were. It is not easy being your writer self publicly. And it’s not easy quieting the mind so you can hear. It’s not easy doing it and it is not easy teaching it.

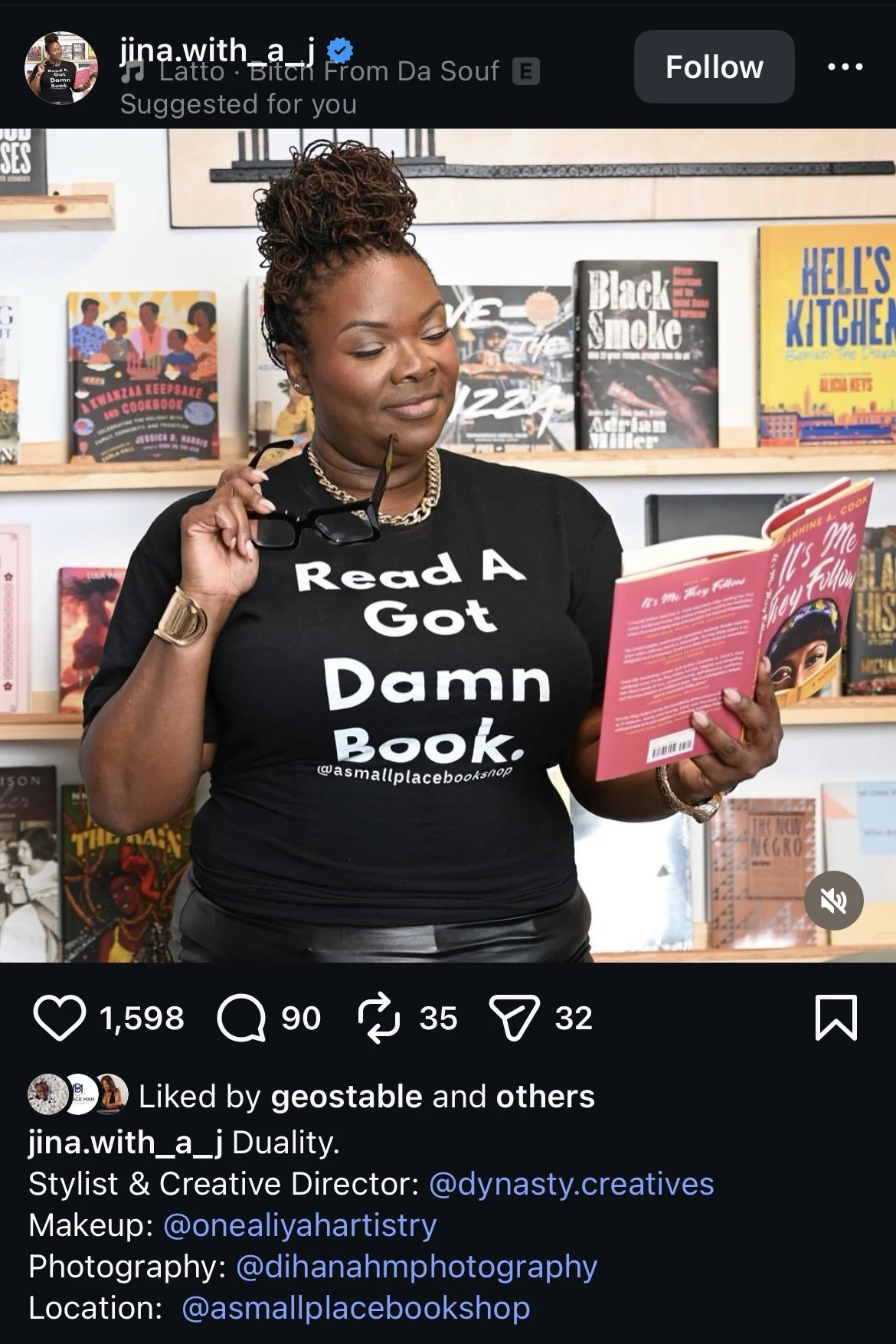

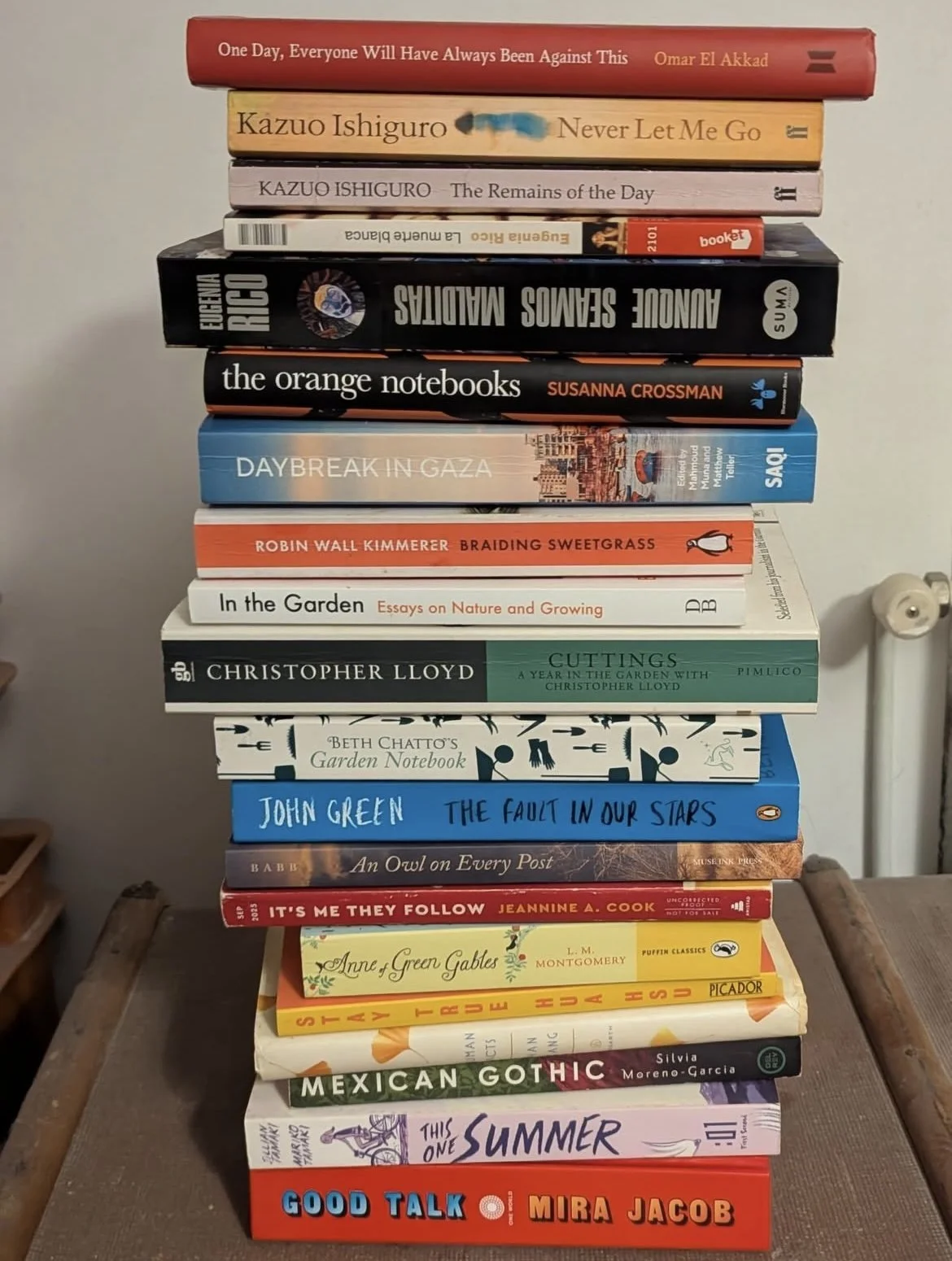

Just quiet yourself. Find your stillness. LISTEN. I am so easily distracted. So it’s like I keep trying to build myself the best environment for me. Silent but filled with people. But I miss my house cause it had fewer distractions. I need a house so my nana can come visit me. All week I became obsessed with facing the fact that eventually I am going to lose my nana. Eventually I am going to lose the last part of the old me. That makes me want to ugly cry and curse and throw things. First August Wilson and now Nana. How can this be. There’s other things I can write. Like I want to turn my book into a series. I probably can do it too. But like being a barista, I don’t know how. See once again that feeling of feeling lost. Passed the baton to Thalia. It’s not an easy job, serving others and yourself. Making space for others and yourself. Meeting their needs while also meeting your own. Hoping for August Wilson to reincarnate himself into someone I can hold, or better yet, someone who can hold me. AHHHHHHHH! AUGUST come back. Please. I miss you in January. And February. Funny how the Philadelphia Film Society and Free Library have asked me to partner on an August Wilson screening. Of course they did. Why me? Because I am his bereaved girlfriend. Maybe I can channel him. August. Oh August. Speak to me. What do you want me to know, hear, see? Take it easy, Jeannine. You have done plenty and you have plenty more to do. You are not alone, I am here with you. I love you too, August. -Jeannine